On Australia and Asia Regarding: “have we forgotten where we live?”

But I have a different answer than Dover to the question where do we live? than “Asia”. That is not the correct answer.

In his June essay on Pearls and Irritations, Bruce Dover laments the pathetic coverage of Australia in Asia. I share this lament, both for fundamental civilisational reasons as well as personal frustration. As regards the latter, I can note that since 1969, 55 years ago, a huge part of my life has been consumed by trying to describe and analyse parts of Asia to Australians (and others).

Most of my energies have been focused on Indonesia, but also some on The Philippines and Asia. I have helped found two magazines looking at Indonesia, including one still surviving on the web although with different politics than the first issues I edited: Inside Indonesia. I have contributed articles on Indonesia to Nation Review under a penname, National Times, The Australian (as ‘special correspondent’), and quite a few in the Canberra Times. I wrote hundreds of articles and reports on Indonesia for Green Left Weekly (and its precursor) between 1981 and 2006.

In the 1970s, I translated the plays and poems of the Indonesian poet and playwright, W.S. Rendra, which were published and performed in Australia in print, on stage and on radio. In the 1980s, I translated the Buru Quartet novels of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, courageously published by Brian Johns then leading Penguin Books Australia. They are now published by Penguin America and I think Penguin Australia have forgotten that they were the first publisher.

I have had books on Indonesia published by Penguin, Verso, Seagull and by ISEAS.

Over the last ten years I have written regularly on the platforms of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies – Yusof Ishak Institute as a Senior Visiting Fellow. ISEAS today provides the only English language platform where people can systematically follow developments in the Southeast Asian Region. Content on the web platforms from the few Australian universities that still maintain them is sporadic at best. I have taught Indonesian studies subjects at the University of Sydney and Victoria University in Melbourne.

I mention these few things just to confirm for the reader where my real-life commitments lie and what therefore I think is important. But I have a different answer than Dover to the question where do we live? than “Asia”. That is not the correct answer. The correct answer is that we live on planet Earth. Our future is not simply tied to the future of Asia. The future, if we have any future, is a common future with all the peoples of the Earth.

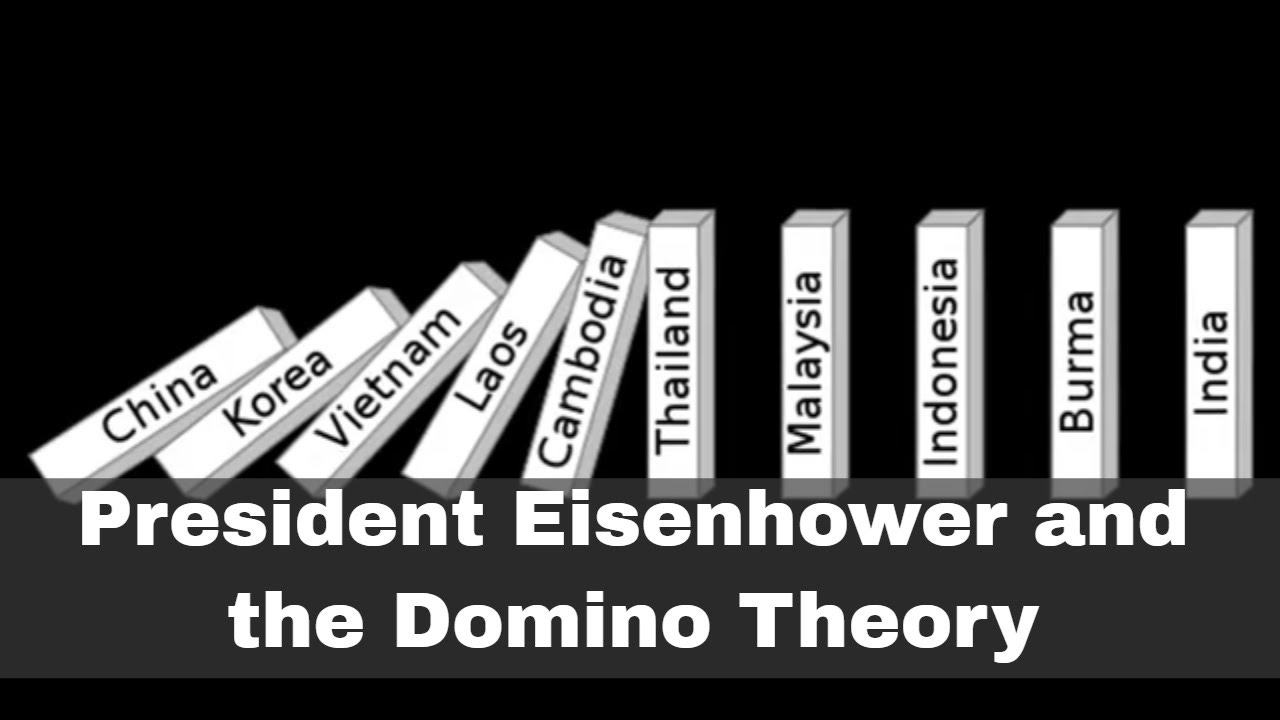

Back in 1969 when I began studying Indonesian language, literature and history at the University of Sydney, the phrase “near North, not Far East” was still regularly quoted, apparently from Sir Robert Menzies. The penny had dropped regarding the proximity of Southeast and East Asia to Australia. The Japanese military expansion to Indonesia and Papua New Guinea during World War 2 had, of course, been a reminder in the framework of a threat. The Cold War years with graphics of giant Red Arrows coming downwards from Yellow China or falling dominoes from one country to another through Southeast Asia deepened that sense of threat. It still there today. Perhaps today it is projected as a Moslem bomb threat from within Indonesia or embodied in the evilly banal assumption in a newsreader’s reference to China as an adversary.

That was one side of the outlook. The other was the sense of solidarity and empathy that evolved among people of my age with the suffering but also the fighting spirit of the Vietnamese people, determined to decide for themselves the future of their country and kick out the Americans, Australians and others. That solidarity and empathy extended then to the whole Third World. Many of us were enthralled with what seem to be the bottoms-up, grass roots development of Mao’s China. The Cuban revolution succeeded.

There was also another ideological framework which was even broader and more enveloping many people in the rich world as they looked at the Third World. It certainly affected me, alongside the impact of the Vietnamese national liberation war. I remember on my desk in my little room at International House at the University of Sydney the three volumes of Gunnar Myrdal’s Asian Drama; An Inquiry into The Poverty of Nations. As more colonies won their independence from their colonial oppressors, they found themselves impoverished, stuck in economic backwardness. How these countries could get out of that backwardness and genuinely develop was a debate that was central to almost all international political discourse, overshadowed only by the question of looming nuclear war.

In Australia, separate and more moderate than the political radicalisation engendered by Vietnam, China or Cuba, empathy and support for Third World economic development was widespread. Organisations like the Freedom from Hunger Campaign and Community Aid Abroad had strong and wide grass-roots presence. There was support for a demand that there be a specific percentage of the Australian GDP allocated to development aid to the developing countries.

All that has disappeared. In mainstream public discussion, the terms “developing countries” and “underdeveloped countries” has disappeared. Replacing these terms is “emerging markets”. For many that is how Asia is perceived: as an emerging market – while at the same time as a source of threat. (China? Indonesia?) Well, it is true that the markets for goods that Australian companies could sell in Asia is growing. The GDPs of most Asian countries consistently grow and have grown for most of their lives as independent countries. With this GDP growth has come the expansion of their urban economies and at least some manufacture, and with that the growth of a middle class. And the middle class is that ‘emerging market’ that can make some Australian business people salivate. One can estimate that maybe 10-15 million Indonesians have a disposable income, after all necessities, of $300 per week. Some necessities would also need imports. This is a sizeable market, especially for a capitalist class that is as small as Australia’s.

The disappearance of the terms “developing countries” and “underdeveloped countries” and their replacement by “emerging markets” basically redefines development as an economy with a growing middle class. The fate and quality of life for the rest of the population disappears from the formula as does the whole concept of development itself. Yes, the United Nations has a set of social indicators which indicates that the Third World (now called the Global South) lags behind in almost all things – with exceptions like Cuba’s outstanding health and education achievements. Discussion of such indicators, however, has no profile any more.

In the case of Australian understanding of Indonesia’s development situation, my estimate that it is close to nil. Nobody in Australia thinks on terms of Indonesia being a terribly poor country with a GDP per capita of only AUD$8k compared to Australia’s AUD$102k. More dramatic is the net wealth per capita for Australia is AUD$617,000 while Indonesia’s is $31,200.

At present growth rates, when will the majority of the Indonesian people have the same quality of consumption as Australians? The answer: under current development strategies: NEVER.

This disparity is what defines the context of all relations between Australia and Indonesia, and Australia and all major countries in Asia, except Japan. There is a problem to solve. Equity. The inequity that exists is a direct consequence of the extended period of colonial domination that began in the 16th century and of the West’s consistent support for post-independence governments in Asia that have accepted that inequity. Only China and Vietnam have succeeded in consolidating governments that have been able to start to remedy that inequity, although not end it.

It is true what Bruce Dover says: for many, Asia is what you fly over to get to Europe or north America. And that applies to the Third World as a whole: the poor countries of the world are what an Australian flies over to get to another (white) rich country.

While the ending of the inequity between rich and poor countries is not seen as a challenge, then the Australian media, either owned by our capitalist class or reflecting its prejudices, will remain uninterested in Asia. Australian universities, awash with soft diplomacy money from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs (DFAT), also do not centre the challenge of ending inequity in their interests in Asia.

Of course, the problem of inequity between Global North and Global South is the problem of the continuing relationship of colonial-originating exploitation of the rich countries over the poor. At least in this respect, it has been an Australian scholar, Samuel King, that has provided the best recent explanation of how that exploitation continues today in his book, Imperialism and the development myth: How rich countries dominate in the twenty-first century One strength, among many, of King’s book is he shows how that even despite China’s amazing developmental achievements, it too remains a victim of this exploitative relationship.

Within this overall context, we cannot expect either the existing Australian media businesses or the Australian universities to initiate a pivot to focusing on the struggle against inequity and exploitation between countries, including Australia and most of Asia.

Australia’s first solidarity relationship with Indonesia originated from Australian trade unions and civil liberty organisations between 1945-49, when scores of trade unions black banned Dutch ships taking soldiers and arms back to Indonesia to recolonise it. But Australian trade unions have shrunk drastically over the last 30 years, are weak, and still under the influence of the now centre-right, neo-liberal Australian Labor Party (ALP). From where can arise an orientation to our Asian neighbours that recognises the challenge of ending exploitation and respond with solidarity and empathy?

I think it can only come from youth – and more and more young Australians do visit Asia, including under schemes funded by DFAT soft diplomacy funding. Many more visit Indonesia on holiday. But very few study Indonesian language or society at school or university. It is true, no doubt, that much of this travel is done as a remedy or therapy for the boredom of Australian suburban existence or working life. Indonesian language and society are often taught in that framework also: something fun, colourful and different from Australia. The vibrancy and difference are, indeed, also something that I too enjoy. So, this increasing engagement also may not generate what is needed for a pivot to struggle against exploitation and inequity as positive a development as it may be.

Across Australia today hundreds of thousands of people are outraged at the inhumanity of the flagrant genocide committed by the Israeli regime against the Palestinian people. This is because it has been impossible to cover up and because what can be seen on real time footage is so obviously planned, cruel and genocidal. It is a positive thing that such outrage has developed. Two things need to happen. First, the outrage needs to build such a strong pressure, that the Australian government cuts all ties with Israel and ceases all military cooperation with Israel’s chief backer, the United States.

But there is a second thing: we must explain why the same outrage is necessary against a system, an aggressively enforced structure of exploitation, that keeps two thirds of the world and economically backward, depriving them a future quality of life. This includes the hundreds of millions in Asia.

Australia, stuck where it is at the arse end of the world, an island off the coast of Asia, originally itself a genocidal white settler colony, now a multi-ethnic nation benefiting from its position in the global imperial structure, faces its own challenge as a nation. Remain a part of the problem or become a part of the solution: a force struggling towards an equitable world, working together with progressive people among its neighbours, in what could only be the most exciting, enriching and liberating collective endeavour to change the whole world.